Mixed models with R

Marc Pépino

December 2022

- Introduction

- Packages

- Simple linear regression

- Mixed-models: varying-intercepts

- Mixed-models: varying-slopes

- LMM: brook charr allometry

- GLMM: brook charr abondance

- NLME: walleye growth curve

- References

Introduction

Linear mixed models (LMM) are natural extension of the simple linear regression and are now among the most standard and powerful techniques use to model ecological data. We first show this extension using simulations as I’m convinced that we well understand a model if we are able to simulate it. Simulations are also a precious help for teaching statistics. Using simulations, we wish to understand the output of mixed models that gives more information than the simple p-values, especially the variance structure of the data. We finally show how to apply mixed models to three cases studies, exploring linear mixed models and their extensions to generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) and non linear mixed models (NLME). At each step (i.e., data download, model fitting, model validation), we will use graphics to visualize what we have in hand. Without graphics, we walk blind and risk straying far from what we think we are modeling. We will explore LMM and their extensions using Pinheiro and Bates (2000) as the main reference book. Other complementary books include, but not limited to, Faraway (2006), Gelman and Hill (2006) for a soft transition to Bayesian modelling, and the Zuur et al. (2009) for practical applications of mixed models to ecological data and, probably, the most popular book consulted by students. An introduction to mixed models could also be found in articles like Wagner et al. (2006), Bolker (2009) or Harrison et al. (2018).

Packages

Wee need the following packages for this workshop. I’m usually as minimalist as possible and upload only the packages we really need. Be particularly careful to the order you upload the packages since some functions could be masked from package to package.

#Packages ####

library(ggplot2) #For graphic visualization

library(readxl) #For downloading Excel data

library(lme4) #For mixed models (most popular)

library(glmmTMB) #For speed up mixed models

library(nlme) #For mixed models (my favorite)

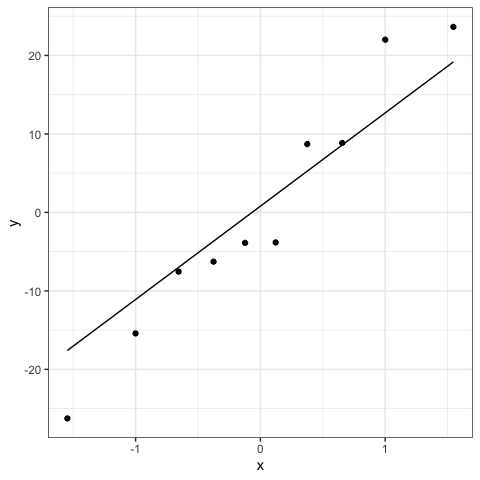

Simple linear regression

The simple linear regression is the starting point to understand mixed models. The regression line is defined by two parameters: the intercept (i.e., the y-value when x is equal to zero) and the slope (i.e., the increase of y when x increases from one unit). To simulate a simple linear regression, we also need to add residuals to y-values. This last step is the most important because it comes from the main assumption: residuals are independent and normally distributed with mean zero and variance ($\sigma^2$) to be estimated from the data. The equation of the simple linear regression could be written as follow:

\[y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \epsilon_i, \epsilon_i \sim N(0,\sigma^2)\]Where $y_i$ and $x_i$ are variables, $\beta_0$ and $\beta_1$ are the parameters (i.e., the intercept and slope, respectively), and $\epsilon_i$ are the residuals.The index $i$ refers to observations.

We first define the parameters of the equation, then the predictor (i.e., x-values) and finally the response variable (i.e., y-values), adding the residuals with an additional parameter: the standard deviation (i.e., $\sigma$). In experimental studies, we can choose to have x-values coming from the uniform distribution. In observational studies, however, x-values generally come from the normal distribution. In this example, we will choose to have x-values coming from the normal distribution. Note that we also need to define how many observations we have in hand (i.e., the sample size: n).

Simulation

Note that in this simulation, we say that $y$ comes from the normal distribution with mean given by the linear equation,$\beta_0 + \beta_1 x$, and standard deviation coming from the residuals, which is equivalent to first add the linear equation and then the residuals.

# Define the parameters of the equation

b0 = 5 # Intercept

b1 = 3 # Slope

sigma = 30 #standard deviation of the residuals

# Define the data

n = 50 #Sample size

x = rnorm(n,mean=125,sd=10)

y = rnorm(n,mean=b0+b1*x,sd=sigma)

dat = data.frame(x,y)

Graphic

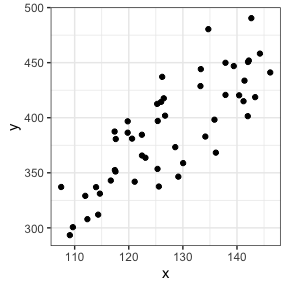

Let’s take a look at our data

# Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y))+

geom_point()+

theme_bw()

Analyses

The code for model fitting is generally quite easy and the shortest part of the exercise.

mod = lm(y~x,data=dat)

Results

The summary function is usually used to explore the output of the model.

summary(mod)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x, data = dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-51.45 -23.78 -3.68 19.78 65.68

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -68.6240 47.3891 -1.448 0.154

x 3.5884 0.3705 9.685 7.15e-13 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 28.3 on 48 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.6615, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6544

F-statistic: 93.8 on 1 and 48 DF, p-value: 7.147e-13

In this example, we see the intercept, the slope (x), but also the estimated standard deviation of the residuals (Residual standard error) and how the variance is explained by the predictor (Multiple R-squared, i.e., the coefficient of determination, $R^2$). We can see that the parameter values are closed of what we have simulated but not exactly the same, especially for the intercept. This is what we expect since we add residuals to y-values. Increasing residuals (i.e., increasing sigma in simulating data) leads to lower fit.

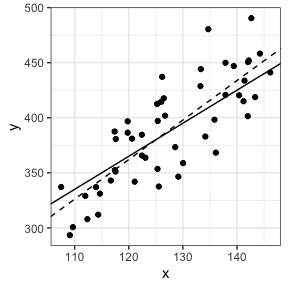

Let’s take a look at our data, adding simulated (solid) and estimated (broken) lines.

# Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y))+

geom_abline(intercept=b0,slope=b1)+

geom_abline(intercept=coef(mod)[1],slope=coef(mod)[2],lty=2)+

geom_point()+

theme_bw()

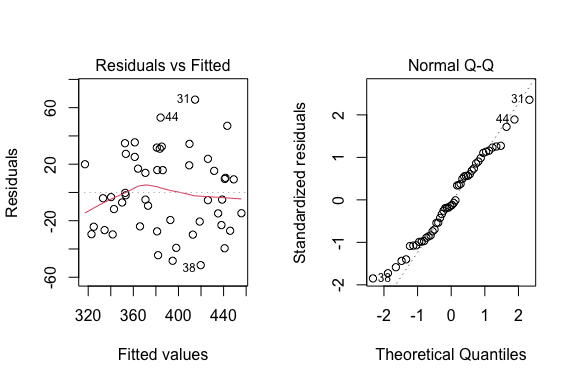

Assumptions

The first plot is to verify the independence of the data and the homogeneity of the residuals. The second plot is to verify the normality of the residuals.

# Model checking

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(mod,which=c(1,2))

Mixed-models: varying-intercepts

The simplest LMM is the varying-intercept model. Because of the presence of grouped data, the main assumption of the independence of the data is violated. Then, LMM comes from a natural extension of the linear regression, assuming than the intercept could vary among groups. This variation is assumed to come from a normal distribution, with mean zero and variance (i.e., $\sigma_{\beta0}^2$) to be estimated from the data. In this way, we obtain a global relationship at the population level (i.e., fixed effects) and deviation at the group level (i.e. random effects).

The equation of LMM with varying-intercept could be written in two steps:

\[y_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + \beta_1 x_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij}, \epsilon_{ij} \sim N(0,\sigma^2)\] \[\beta_{0j} = \beta_0 + b_{0j}, b_{0j} \sim N(0,\sigma_{\beta0}^2)\]Where $y_{ij}$ and $x_{ij}$ are variables, $\beta_0$ and $\beta_1$ are the parameters (the intercept and slope, respectively) at the population level, $\beta_{0j}$ are the intercepts at the group level, $b_{0j}$ are the group level residuals of the intercept, and $\epsilon_{ij}$ are the level-one residuals.The index $j$ refers to group level. The index $i$ refers to observations.

Simulation

To simulate LMM, we need an additional parameter, the standard deviation of the intercept at the group level (i.e., $\sigma_{\beta0}$). Since we need to simulate the data at each group level,we will define the x-values for each group and then loop the simulation for all groups.

# Define the parameters of the equation

b1 = 3 #slope

b0 = 5 #intercept

sigma = 10 #sd for residuals

sigmab0 = 20 #sd for intercepts

b0j = rnorm(n=1000,mean=0,sd=sigmab0)

# Define the data

ng = 10 #number of group

nj = sample(20:40,ng,replace=TRUE) #sample size in each group

xmean = runif(ng,-25,25) #x mean in each group

xsd = runif(ng,5,10) #x sd in each group

# Loop for all groups

dat = data.frame()

for(j in 1:ng){

x = rnorm(nj[j],mean=xmean[j],sd=xsd[j])

y = rnorm(nj[j],mean=b0+b0j[j]+b1*x,sd=sigma)

g = rep(j,nj[j])

dat = rbind(dat,data.frame(x,y,g))

}

dat$g = as.factor(dat$g)

Graphic

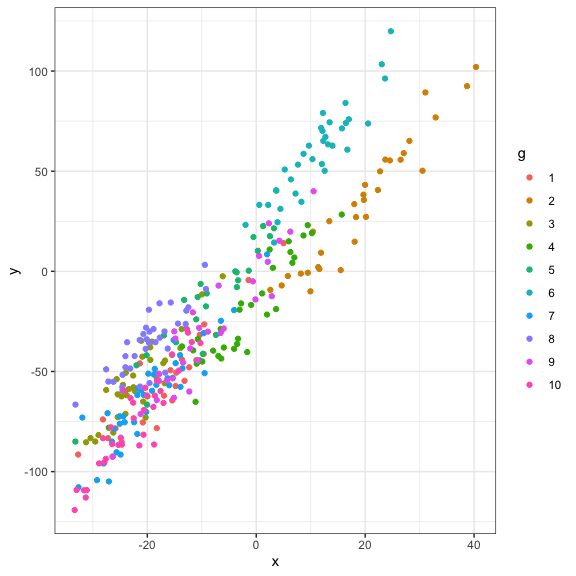

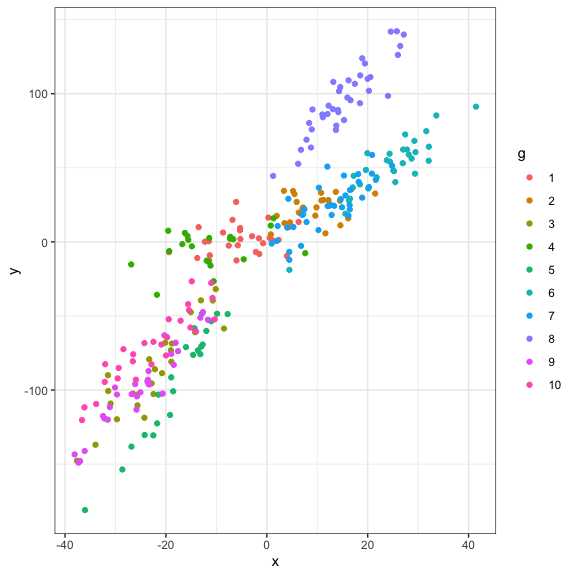

Let’s take a look at our data

#Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y,col=g))+

geom_point()+

theme_bw()

Analyses

Traditionally we could analyse this type of data using ANCOVA, using the grouping factor as an additional predictor. However, a more powerful technique is to use LMM with varying-intercept. Using the nlme package, the random argument specifies the intercept (i.e., 1) and the grouping factor (i.e., g in this example) as follow:

#Analyses: ANCOVA

mod = lm(y~x+g,data=dat)

summary(mod)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x + g, data = dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-23.7049 -6.1446 0.3523 6.7870 26.3402

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -4.58808 2.32945 -1.970 0.049769 *

x 3.04646 0.07239 42.084 < 2e-16 ***

g2 -20.59491 3.71571 -5.543 6.35e-08 ***

g3 15.36780 2.61833 5.869 1.12e-08 ***

g4 -9.37524 2.80239 -3.345 0.000922 ***

g5 15.12837 2.84610 5.315 2.03e-07 ***

g6 29.96195 3.27074 9.161 < 2e-16 ***

g7 2.48753 2.54925 0.976 0.329926

g8 28.64816 2.59083 11.058 < 2e-16 ***

g9 2.40887 2.76159 0.872 0.383729

g10 -1.18766 2.62787 -0.452 0.651621

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 9.788 on 312 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.96, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9587

F-statistic: 749.1 on 10 and 312 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

#Analyses: Mixed models with nlme package

mod = lme(y~x,random=~1|g,data=dat)

summary(mod)

Linear mixed-effects model fit by REML

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik

2439.092 2454.178 -1215.546

Random effects:

Formula: ~1 | g

(Intercept) Residual

StdDev: 15.93838 9.787311

Fixed effects: y ~ x

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) 1.601332 5.110372 312 0.31335 0.7542

x 3.035387 0.071049 312 42.72226 0.0000

Correlation:

(Intr)

x 0.125

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-2.41041756 -0.62668163 0.03215744 0.70114206 2.67355343

Number of Observations: 323

Number of Groups: 10

The interpretation of the ANCOVA could be tedious, especially as the number of groups increases. The interpretation of the mixed model is more straightforward, at least for the fixed effects…

Results

We can easily retrieve the summary output using different functions and compare the results to simulated parameters. This exercise is particularly helpful to see how well the model fits to the data. This could be helpful, for example, to found the best sampling design before collecting ecological data (e.g., Pépino et al. 2016). Especially, the intervals functions gives the confidence intervals of parameter estimates (the default is 95%), which can be used to report the final result of the model.

fixef(mod) #The coefficient of the fixed effects (estimates)

(Intercept) x

1.601332 3.035387

ranef(mod) #b0j estimates

(Intercept)

1 -6.274000

2 -26.251615

3 8.845424

4 -15.420527

5 8.704950

6 23.639338

7 -3.881986

8 22.007652

9 -3.825922

10 -7.543314

VarCorr(mod) #the variance covariance structure (sigmab0 and sigma estimates)

g = pdLogChol(1)

Variance StdDev

(Intercept) 254.03190 15.938378

Residual 95.79145 9.787311

intervals(mod) #95 confidence intervals of parameter estimates

Approximate 95% confidence intervals

Fixed effects:

lower est. upper

(Intercept) -8.453819 1.601332 11.656483

x 2.895591 3.035387 3.175184

Random Effects:

Level: g

lower est. upper

sd((Intercept)) 9.976875 15.93838 25.46207

Within-group standard error:

lower est. upper

9.048780 9.787311 10.586118

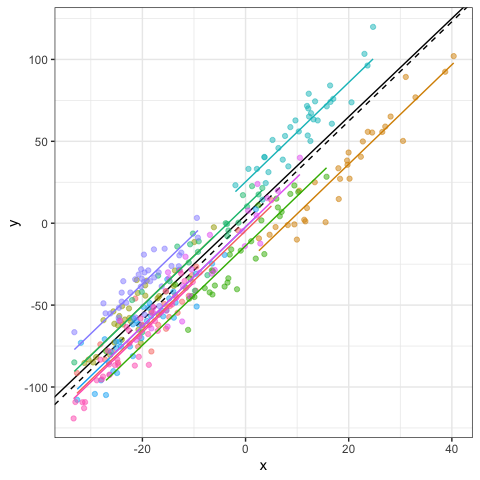

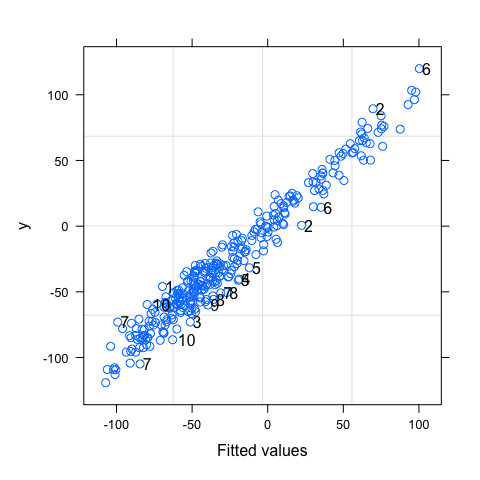

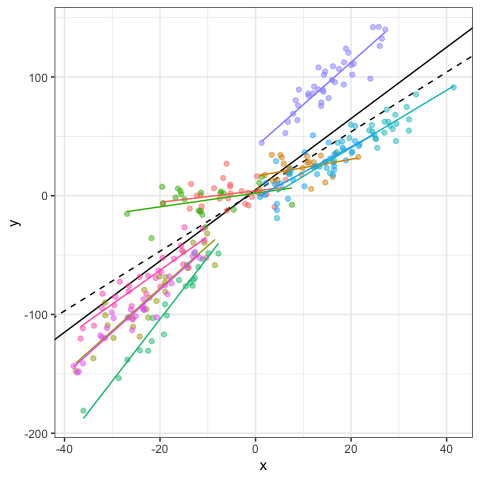

We can also add the fitted and residuals values to the original data frame using the fitted and residuals function, respectively. This is particularly helpful for checking model assumptions or illustrating model fitting. Here, black and color lines refer to regression lines at the population and group levels, respectively.

dat$fit = fitted(mod) #fitted values

dat$res = residuals(mod) #residuals values

# Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y,col=g))+

geom_abline(intercept=b0,slope=b1)+

geom_abline(intercept=fixef(mod)[1],slope=fixef(mod)[2],lty=2)+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

geom_line(aes(x=x,y=fit,col=g),linewidth=1)+

#facet_wrap(~g)+ #Optional

theme_bw()+

theme(legend.position="none")

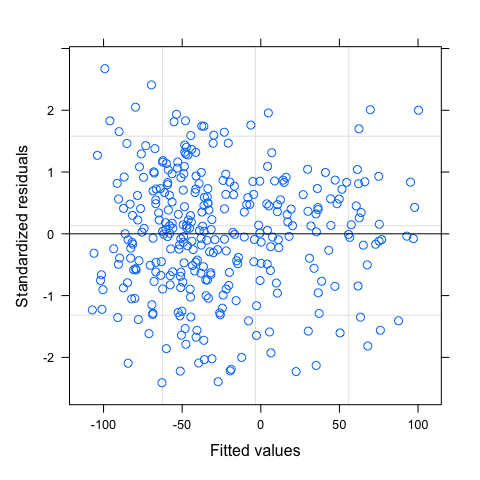

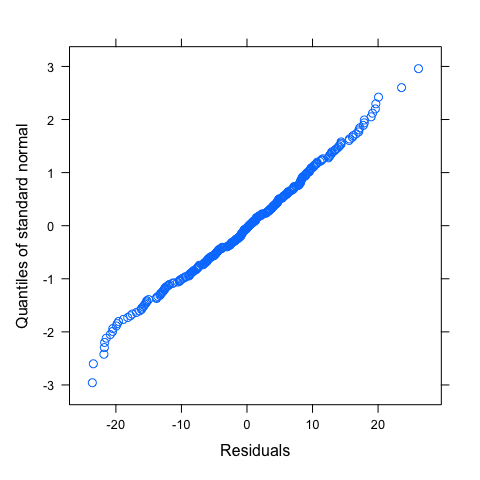

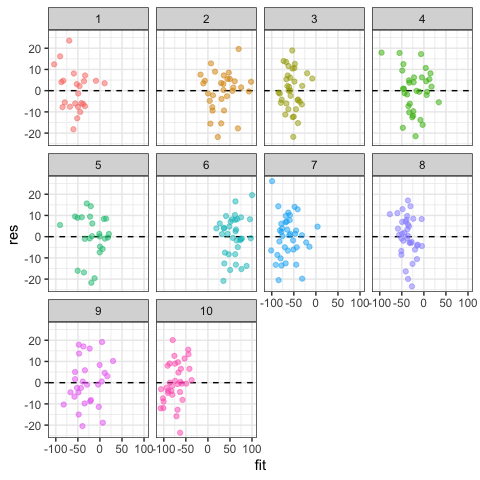

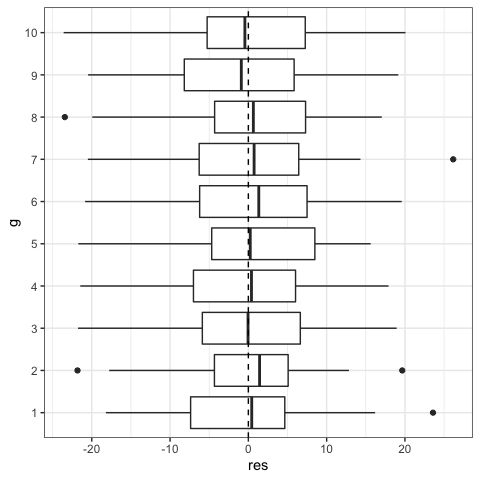

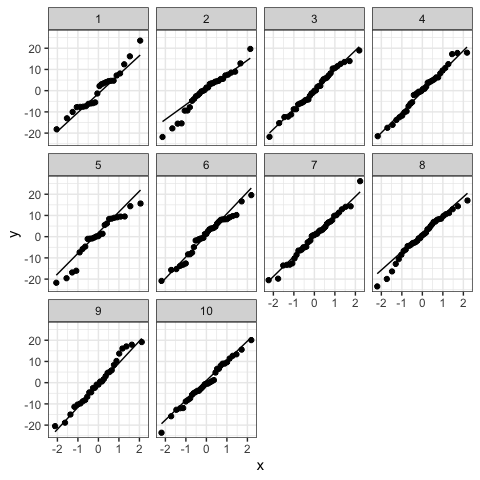

Assumptions

There are tow main assumptions.

Assumption 1: within-group errors

The within-group errors are independent and identically normally distributed, with mean zero and variance to be estimated, and they are independent of the random effects.

You can used default functions to verify this first assumption. Note that this assumption should be verify at the group level. You can also have an rough idea of the goodness-of-fit by plotting fitted versus observed values.

#Homogeneity of residuals

plot(mod)

plot(mod,g~resid(.,type="p"),abline=0)

plot(mod,resid(.,type="p")~fitted(.)|g,abline=0,lty=2)

#Normality of residuals

qqnorm(mod,~resid(.))

#Some idea of goodness-of-fit

plot(mod,y~fitted(.),id=0.05,adj=-0.3)

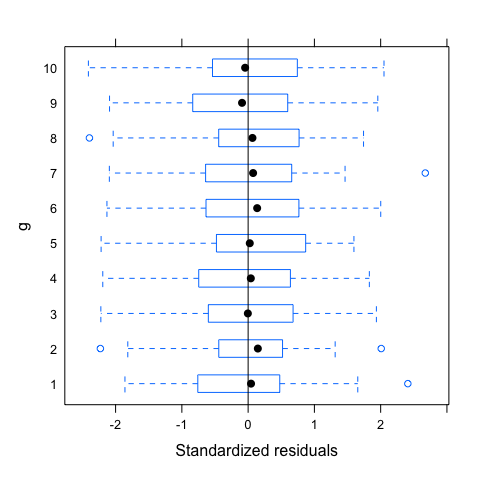

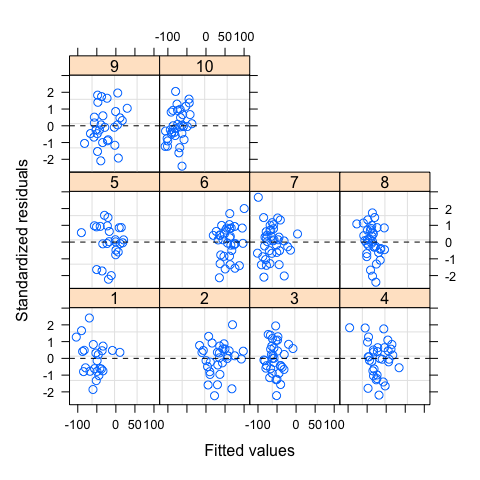

After adding residuals and fitted values to the data frame, you can also reproduce similar graphs using ggplot.

#Homogeneity of residuals

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=fit,y=res,col=g))+

geom_hline(yintercept=0,lty=2)+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

facet_wrap(~g)+

theme_bw()+

theme(legend.position="none")

#Boxplot could also be used to see variation of residuals among groups

#You could also explore relationship between residuals and predictors

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=g,y=res))+

geom_boxplot()+

geom_hline(yintercept=0,lty=2)+

coord_flip()+

theme_bw()

#Normality of residuals

ggplot(dat,aes(sample = res))+

stat_qq()+

stat_qq_line()+

facet_wrap(~g)+#optional

theme_bw()

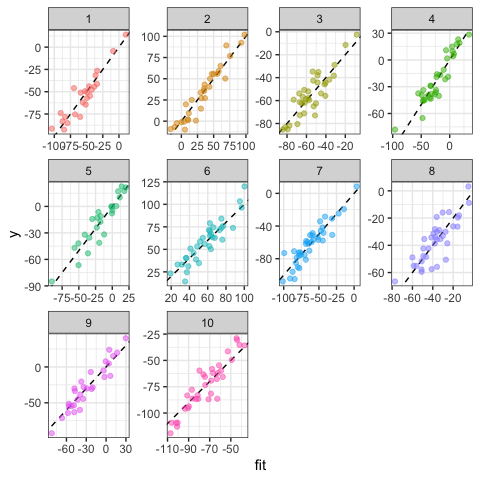

#Prediction: a rough idea of goodness-of-fit

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=fit,y=y,col=g))+

geom_abline(intercept=0,slope=1,lty=2)+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

facet_wrap(~g,scale="free")+

theme_bw()+

theme(legend.position="none")

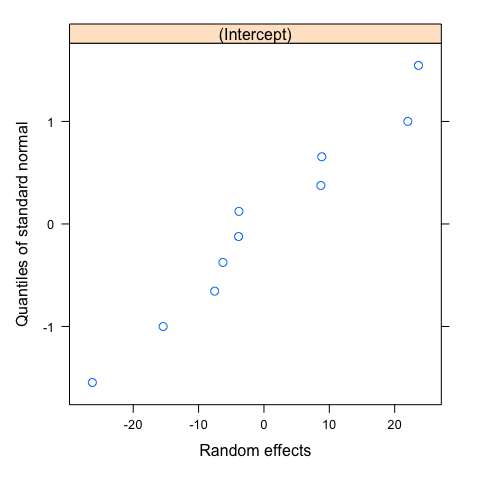

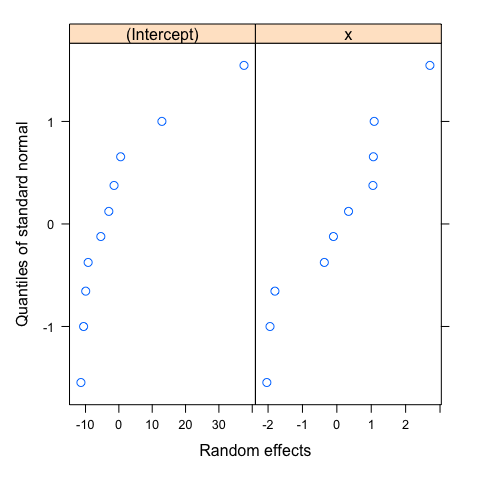

Assumption 2: random effects

The random effects are normally distributed, with mean zero and covariance matrix (not depending on the group) and are independent for different groups.

As before, you can use default functions or customize graphic output using ggplot. Note that with 10 groups, it is more difficult to evaluate carefully this second assumption.

#First option: default functions

#Normality of random effects

qqnorm(mod,~ranef(.))

#Second option: ggplot

ran = ranef(mod)

ggplot(ran,aes(sample = ran[,1]))+

stat_qq()+

stat_qq_line()+

theme_bw()

Violation of assumptions could include dependencies or heteroscedasticity among the within-group errors that can be modeled with correlation structure or the specification of the Variance-Covariance matrices for the random effects, respectively. Even if I encourage to adequately specify how to model the fixed and random effects, mixed models are generally robust to violations of these assumptions (Schielzeth et al. 2020).

Intraclass correlation

The intraclass correlation (ICC) is the proportion of the total variation that is among groups (Faraway 2006, Gelman and Hill 2007). The ICC could be calculated in varying-intercept models as follow:

\[\frac{\sigma_{\beta0}^2} {\sigma^2 + \sigma_{\beta0}^2}\]Where $\sigma^2 + \sigma_{\beta0}^2$ is the total variation and $\sigma_{\beta0}^2$, the variation among groups.

The ICC is thus the variation among groups divided by the total variation. The ICC ranges from 0 (all variation withing groups) to 1 (all variation among groups). You can read Reyjol et al. (2008) for an ecological application. Extension of ICC could also be found in animal behavior studies for the estimation of repeatability (e.g., Dingemanse and Dotcherman 2013, Allegue et al. 2017).

variation = as.numeric(VarCorr(mod)[,1])

ICC = variation[1]/sum(variation)

ICC

[1] 0.7261719

sigmab0^2/(sigmab0^2+sigma^2) #Predicted value of ICC based on simulated values

[1] 0.8

Mixed-models: varying-slopes

Now we can assume that not only the intercept could vary among groups, but also the slope. We could also assume that only the slope varies among groups and the intercept is fixed but, as many ecological data could vary both in intercept and slope, we will not explore this option here. This variation in slope is assumed to come from a normal distribution, with mean zero and variance ($\sigma_{\beta1}^2$) to be estimated from the data.

The equation of LMM with varying intercept and slope could be written as follow:

\[y_{ij} = \beta_{0j} + \beta_{1j} x_{ij} + \epsilon_{ij}, \epsilon_{ij} \sim N(0,\sigma^2)\] \[\beta_{0j} = \beta_0 + b_{0j}, b_{0j} \sim N(0,\sigma_{\beta0}^2)\] \[\beta_{1j} = \beta_1 + b_{1j}, b_{1j} \sim N(0,\sigma_{\beta1}^2)\]Where $y_{ij}$ and $x_{ij}$ are variables, $\beta_0$ and $\beta_1$ are the parameters (the intercept and slope, respectively) at the population level, $\beta_{0j}$ are the intercepts at the group level, $\beta_{1j}$ are the slopes at the group level, $b_{0j}$ are the group level residuals of the intercept, $b_{1j}$ are the group level residuals of the slope, and $\epsilon_{ij}$ are the level-one residuals.The index $j$ refers to group level. The index $i$ refers to observations. Important: random intercept and random slope are not assumed to be independent from each other, which is taking into account by their covariance matrix. For simplicity, we will assume that they are independent in the following simulations.

Simulations

The simulation look like the varying-intercept mixed model. The only difference is that we add an additional parameter, the standard deviation ($\sigma_{\beta1}$) to take into account that the slope could vary among groups.

dat = data.frame()

# Define the parameters of the equation

b1 = 3 #slope

b0 = 5 #intercept

sigma = 10 #sd for residuals

sigmab0 = 20 #sd for intercepts (try 20)

sigmab1 = 1 #sd for slopes (try 1 or 0.2 or 0)

b0j = rnorm(n=1000,mean=0,sd=sigmab0)

b1j = rnorm(n=1000,mean=0,sd=sigmab1)

# Define the data

ng = 10 #number of group

nj = sample(20:40,ng,replace=TRUE) #sample size in each group

xmean = runif(ng,-25,25) #x mean in each group

xsd = runif(ng,5,10) #x sd in each group try: (5,10) or (1) or 30

# Loop for all groups

dat = data.frame()

for(j in 1:ng){

x = rnorm(nj[j],mean=xmean[j],sd=xsd[j])

y = rnorm(nj[j],mean=b0+b0j[j]+(b1+b1j[j])*x,sd=sigma)

g = rep(j,nj[j])

dat = rbind(dat,data.frame(x,y,g))

}

dat$g = as.factor(dat$g)

Graphic

Let’s take a look at our data

#Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y,col=g))+

geom_point()+

theme_bw()

Analyses

As for LMM with varying-intercept, we start with a model fitting using ANCOVA, but with an interaction term. The varying-slope model is specified by adding the predictor x in the random argument. Note that the ANCOVA output could be particularly difficult to interpret, especially as the number of groups increases. LMM output is more straightforward, with the same number of parameters whatever the number of groups.

# Analyses: ANCOVA

mod = lm(y~x*g,data=dat)

summary(mod)

Call:

lm(formula = y ~ x * g, data = dat)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-27.410 -6.494 -0.313 6.256 28.988

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 3.6850 2.4732 1.490 0.13742

x 0.4027 0.3120 1.291 0.19793

g2 14.7585 4.9330 2.992 0.00304 **

g3 -11.0255 6.7928 -1.623 0.10576

g4 -2.3594 4.5790 -0.515 0.60679

g5 -1.6848 6.5532 -0.257 0.79731

g6 -13.1434 6.5245 -2.014 0.04498 *

g7 -5.7461 4.4803 -1.283 0.20079

g8 39.8874 5.0984 7.824 1.25e-13 ***

g9 -11.9828 7.2724 -1.648 0.10061

g10 -10.5213 6.5113 -1.616 0.10732

x:g2 0.1196 0.5088 0.235 0.81440

x:g3 3.1410 0.4117 7.629 4.34e-13 ***

x:g4 0.1057 0.4168 0.253 0.80010

x:g5 4.9061 0.4472 10.971 < 2e-16 ***

x:g6 2.0745 0.3937 5.269 2.86e-07 ***

x:g7 1.7577 0.4126 4.260 2.85e-05 ***

x:g8 3.0249 0.4116 7.350 2.51e-12 ***

x:g9 3.1552 0.4059 7.773 1.73e-13 ***

x:g10 2.4086 0.4009 6.009 6.21e-09 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 10.17 on 263 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9803, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9789

F-statistic: 688 on 19 and 263 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

# Analyses: Mixed models with nlme package - random intercept

mod0 = lme(y~x,random=~1|g,data=dat)

summary(mod0)

Linear mixed-effects model fit by REML

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik

2343.084 2357.637 -1167.542

Random effects:

Formula: ~1 | g

(Intercept) Residual

StdDev: 29.89671 13.88851

Fixed effects: y ~ x

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) -4.228197 9.504821 272 -0.444848 0.6568

x 2.619327 0.117580 272 22.276956 0.0000

Correlation:

(Intr)

x 0.053

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-3.791434759 -0.590994740 -0.006061655 0.640791495 2.420196655

Number of Observations: 283

Number of Groups: 10

# Analyses: Mixed models with nlme package - random intercept and slope

mod1 = lme(y~x,random=~x|g,data=dat)

summary(mod1)

Linear mixed-effects model fit by REML

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik

2197.994 2219.824 -1092.997

Random effects:

Formula: ~x | g

Structure: General positive-definite, Log-Cholesky parametrization

StdDev Corr

(Intercept) 15.847055 (Intr)

x 1.590983 -0.05

Residual 10.166360

Fixed effects: y ~ x

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) 3.512384 5.260836 272 0.667647 0.5049

x 2.513745 0.510795 272 4.921242 0.0000

Correlation:

(Intr)

x -0.036

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-2.76861646 -0.63737211 -0.02064573 0.62375233 2.86482177

Number of Observations: 283

Number of Groups: 10

Results

As for the varying-intercept mixed model, we can compare model estimates with simulated values using the same functions!

fixef(mod1) #The coefficient of the fixed effects (estimates)

(Intercept) x

3.512384 2.513745

ranef(mod1) #b0j estimates

(Intercept) x

1 0.5730601 -2.03206100

2 13.0055977 -1.80691304

3 -9.9867624 1.06178060

4 -1.3780864 -1.93847817

5 -3.1706913 2.69934276

6 -11.3913918 -0.09622784

7 -5.4006808 -0.36205703

8 37.5826831 1.04759948

9 -10.6252539 1.08523496

10 -9.2084743 0.34177928

VarCorr(mod1) #the variance covariance structure

g = pdLogChol(x)

Variance StdDev Corr

(Intercept) 251.129159 15.847055 (Intr)

x 2.531227 1.590983 -0.05

Residual 103.354876 10.166360

intervals(mod1) #95 confidence intervals of parameter estimates

Approximate 95% confidence intervals

Fixed effects:

lower est. upper

(Intercept) -6.844750 3.512384 13.86952

x 1.508131 2.513745 3.51936

Random Effects:

Level: g

lower est. upper

sd((Intercept)) 9.5512907 15.84705522 26.2926935

sd(x) 0.9850315 1.59098298 2.5696913

cor((Intercept),x) -0.6125874 -0.04963095 0.5467327

Within-group standard error:

lower est. upper

9.334299 10.166360 11.072591

And the same code for plotting!

dat$fit = fitted(mod1) #fitted values

dat$res = residuals(mod1) #residuals values

# Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=x,y=y,col=g))+

geom_abline(intercept=b0,slope=b1)+

geom_abline(intercept=fixef(mod1)[1],slope=fixef(mod1)[2],lty=2)+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

geom_line(aes(x=x,y=fit,col=g),linewidth=1)+

#facet_wrap(~g)+ #Optional

theme_bw()+

theme(legend.position="none")

Testing random component

How to choose between random intercept or random slope models ? An easy way is to compare the two models using log-likelihood ratio test or comparing information criteria like Aikaike Information Criteria (AIC). Note that you have to use REML method to compare random effect and ML method to compare fixed effects (Zuur et al. 2009). You can also repeat the simulation using $\sigma_{\beta1} = 0.1$ and see if you obtain the same conclusion!

mod0 = lme(y~x,random=~1|g,data=dat,method="REML")

mod1 = lme(y~x,random=~x|g,data=dat,method="REML")

anova(mod0,mod1)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mod0 1 4 2343.084 2357.637 -1167.542

mod1 2 6 2197.994 2219.824 -1092.997 1 vs 2 149.0896 <.0001

A short note on grouped data. The groupedData function in the nlme package can be used to defined how your data are grouped and speed up model fitting and visualization. Grouped data are also useful to explore different structure of the variance-covariance matrix. In this simulation example, we did not assume any correlation between the slope and intercept of the random component, with can be specify using the pdDiag function. We repeat the preceding models, starting with the random intercept model and then updating this model using the update function. We then compare the models as before using the anova function.

#Grouped data and update function of the nlme package

datG = groupedData(y~x|g,data=dat)

mod0 = lme(y~x,random=~1|g,data=datG,method="REML")

mod1 = update(mod0,random=~x)

mod1diag = update(mod0,random=pdDiag(~x))

anova(mod0,mod1diag,mod1)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mod0 1 4 2343.084 2357.637 -1167.542

mod1diag 2 5 2196.014 2214.206 -1093.007 1 vs 2 149.06951 <.0001

mod1 3 6 2197.994 2219.824 -1092.997 2 vs 3 0.02011 0.8872

To be consistent with the simulation, you should select the model with the random slope and a diagonal variance-covariance matrix (i.e., mod1diag), but conclusions could differ depending of your simulated data…

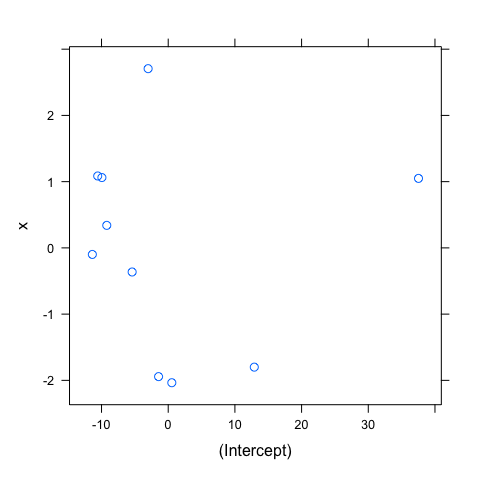

Assumptions

As for the varying-intercept model, the same assumptions applied and could be verify in the same way. You could thus verify these assumptions using the same code. I just show here the scatter plot of the estimated random effects. This plot is particularly useful to visualize the correlation between the intercept and slope of the random component, suggesting which variance-covariance matrix should be used. I also reproduce the normal Q-Q plots of the random effects to emphasize that the normality should be checked for both intercept and slope, but again, with only 10 groups, this assumption is difficult to verify.

#Correlation between random effects

pairs(mod1diag,~ranef(.))

#Normality of random effects

qqnorm(mod1diag,~ranef(.))

Further readings

How total variation in LMM is explained is less straightforward than in linear regressions. For an overview of the indices and available tools, you can consult Nakagawa and Schielzeth (2013), Johnson (2014),or Nakagawa et al. (2017).

How to well include the hierarchical structure of your data (e.g. nested or crossed design), you can consult Schielzeth and Nakagawa (2013) or Harrison et al. (2018).

Finally, before to explore how to fit mixed models to case studies, it is important to read Zuur et al. (2016), a practical guide for conducting and presenting results of regression-types analyses (e.g., see Fig. 1 in the original article). We outline here that model fitting arrives only at the step 6 (among the 10 steps recommended). Thinking (and stating) a relevant ecological question (step 1) and ensuring we have the right data in hand to answer it (step 2) are the primary initial steps that any statistical models can compensate…

LMM: brook charr allometry

The database could be found here: https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.p2k02

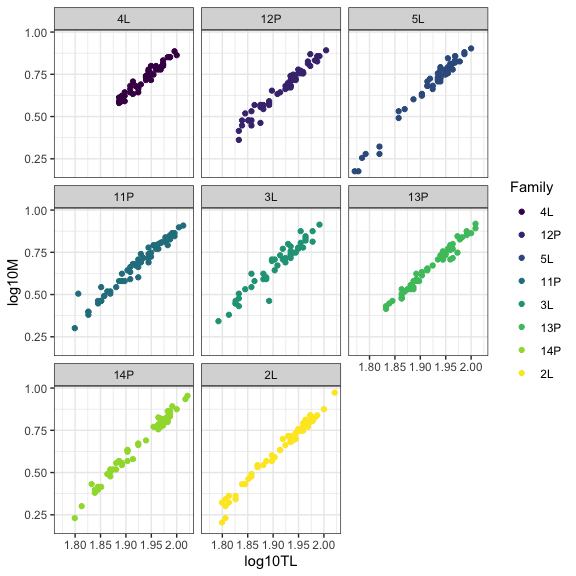

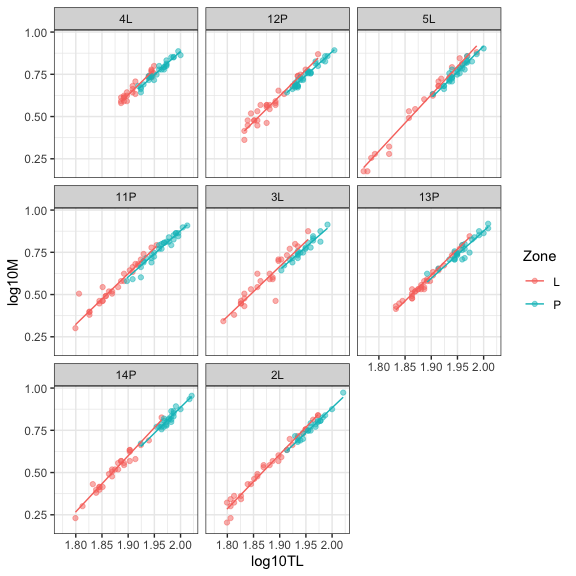

In this example, we will explore the relationship between total length and mass in brook charr. Details of the sampling design could be found in the original article (Pépino et al. 2018). In brief, height families were raised in laboratory and were placed in lake enclosures for growth in summer in two distinct habitats (i.e., littoral or pelagic habitats).

Download and explore data

dat = read_excel("Data/Pepino_et_al_Original_Data.xlsx")

#Transform the total length and mass variables

dat$log10TL = log10(dat$Length_Final)

dat$log10M = log10(dat$Mass_Final)

datG = groupedData(log10M~log10TL|Family,data=dat)

#Visualization

ggplot(data=datG,aes(x=log10TL,y=log10M,col=Family))+

geom_point()+

facet_wrap(~Family)+

theme_bw()

Blind linear mixed model

Many students try the simplest linear mixed model, taking into account the non-independence of the data. We will see how to go further in modelling the variability of ecological data.

#Analyses

mod0 = lme(log10M~log10TL,random=~1|Family,data=datG)

#Results

summary(mod0)

Linear mixed-effects model fit by REML

Data: datG

AIC BIC logLik

-1778.77 -1762.487 893.385

Random effects:

Formula: ~1 | Family

(Intercept) Residual

StdDev: 0.01990289 0.0297343

Fixed effects: log10M ~ log10TL

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

(Intercept) -4.862396 0.05393961 426 -90.14519 0

log10TL 2.881259 0.02784003 426 103.49337 0

Correlation:

(Intr)

log10TL -0.991

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-5.66116458 -0.54323068 -0.03043674 0.53004392 5.58488220

Number of Observations: 435

Number of Groups: 8

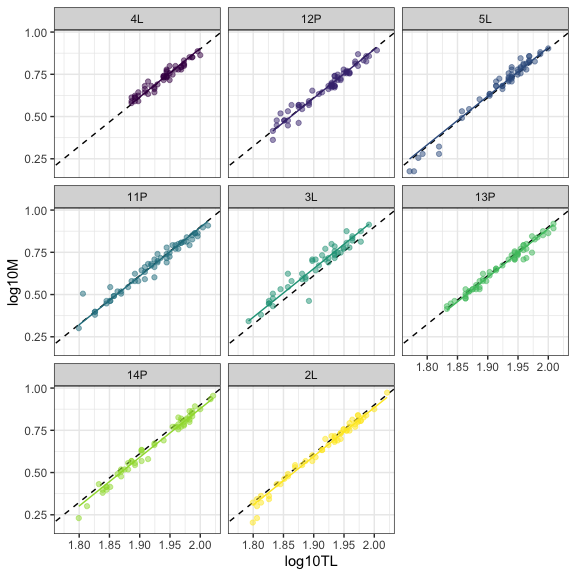

Let’s take a look at our data, adding the population (broken) and family-specific (solid) regression lines.

#Visualization

datG$fit = fitted(mod0)

datG$res = residuals(mod0)

ggplot(data=datG,aes(x=log10TL,y=log10M,col=Family))+

geom_abline(intercept=fixef(mod0)[1],slope=fixef(mod0)[2],lty=2)+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

geom_line(aes(y=fit),linewidth=1)+

facet_wrap(~Family)+ #Optional

theme_bw()+

theme(legend.position="none")

Do we stop the modelling here ?

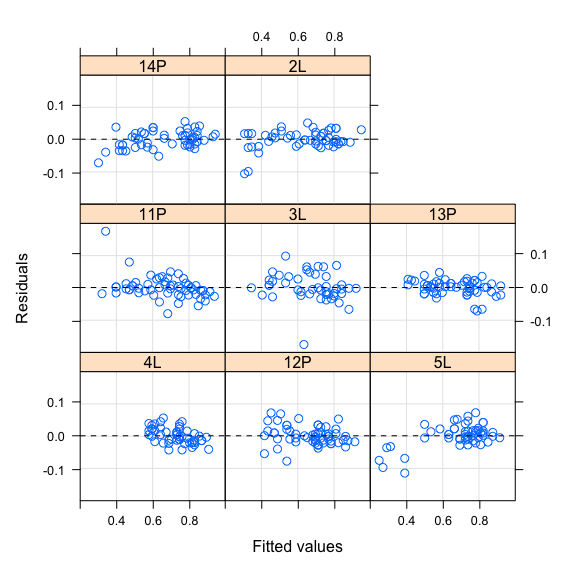

Assumptions

We can’t stop without checking at the assumptions of the model. We first check for the homogeneity of residuals.

#Homogeneity of residuals

plot(mod0,resid(.)~fitted(.)|Family,abline=0,lty=2)

Do we stop the modelling here ?

Random effects

The last plots show patterns in residuals. For example, residuals seem to increase with fitted values for families 14P and 5L, and decrease for family 4L, suggesting that including random slope in model could be useful to improve model fit. This graphical approach could be confirmed by testing the random component according to the approach suggested by Zuur et al. (2009). Following the Zuur’s approach, we start with the full model (i.e., including all variables with their interaction) and test to the random component (i.e., intercept and slope) with the REML method. Technically, model comparison or graphical inspection of the residuals should converge to the same specification of the final model.

modfullI = lme(log10M~log10TL*Zone,random=~1|Family,data=datG)

modfullS = lme(log10M~log10TL*Zone,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG)

anova(modfullI,modfullS)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

modfullI 1 6 -1842.539 -1818.142 927.2695

modfullS 2 8 -1869.018 -1836.490 942.5092 1 vs 2 30.47943 <.0001

Both AIC and log-likelihood ratio test show that we should include random slope.

Do we stop the modelling here ?

Fixed effects

Following the Zuur’s approach, we continue with comparing competing models differing in their fixed component using the ML method.

mod0 = lme(log10M~log10TL,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG,method="ML")

mod1 = lme(log10M~log10TL+Zone,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG,method="ML")

mod2 = lme(log10M~log10TL*Zone,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG,method="ML")

anova(mod0,mod1,mod2)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mod0 1 6 -1825.685 -1801.233 918.8425

mod1 2 7 -1887.127 -1858.600 950.5635 1 vs 2 63.44192 <.0001

mod2 3 8 -1893.485 -1860.883 954.7427 2 vs 3 8.35833 0.0038

Both AIC and log-likelihood ratio test show that Model 2, including the two variables and their interaction, is the best model.

Do we stop the modelling here ?

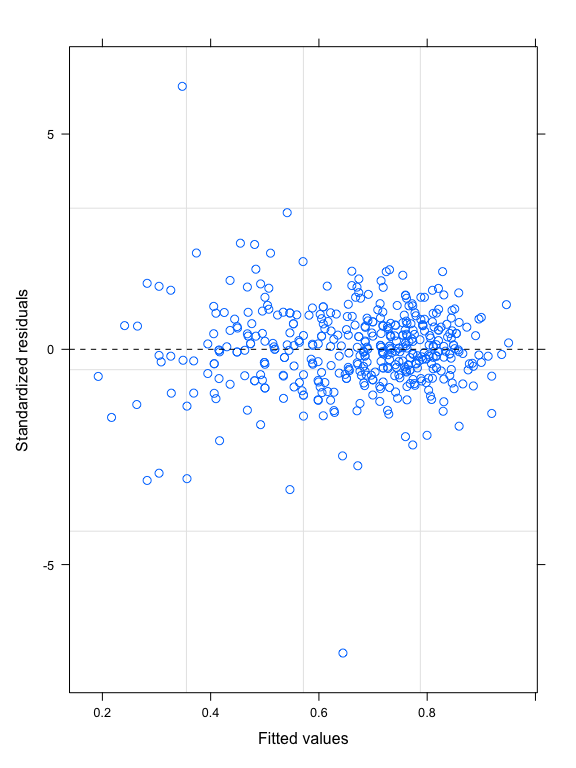

Modelling heteroscedasticity

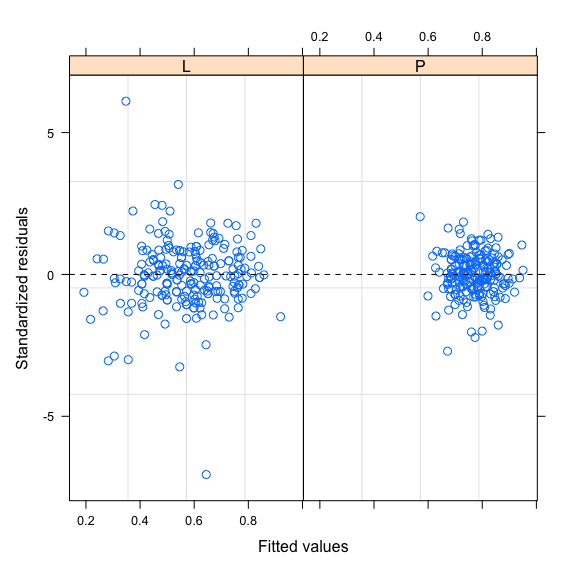

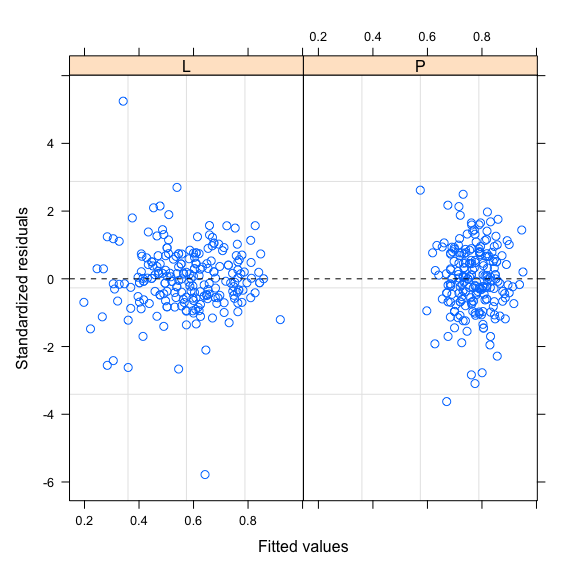

Let’s take a look at the homogeneity of the residuals.

mod2 = lme(log10M~log10TL*Zone,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG,method="REML")

plot(mod2,resid(.,type="p")~fitted(.),abline=0,lty=2)

This plot shows that the variability of the residuals is higher for low fitted values, meaning heteroscedasticity of the residuals. This heteroscedasticity seems to come from different variation of the residuals according to the Zone variable, as shown in the plot below:

plot(mod2,resid(.,type="p")~fitted(.)|Zone,abline=0,lty=2)

We can model this heteroscedasticity using the weights argument and the varIdent function as follow:

mod2H = lme(log10M~log10TL*Zone,random=~log10TL|Family,data=datG,method="REML",

weights = varIdent(form = ~ 1|Zone))

anova(mod2,mod2H)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mod2 1 8 -1869.018 -1836.490 942.5092

mod2H 2 9 -1915.376 -1878.781 966.6881 1 vs 2 48.3578 <.0001

plot(mod2H,resid(.,type="p")~fitted(.)|Zone,abline=0,lty=2)

Model comparison based on AIC and log-likelihood ratio test show that modelling heteroscedasticity improves model fit. Residual variability is also more homogeneous in the two habitats. After choosing the better random and fixed components and including the Zone variable to model heteroscedasticity, we now have a model that better captures the data variability. We can stop the modelling here.

Results

We can then report the results of the best model, first by reporting the parameter estimates and their confidence intervals and then illustrating this result on a plot.

intervals(mod2H)

Approximate 95% confidence intervals

Fixed effects:

lower est. upper

(Intercept) -5.6004388 -5.3142985 -5.0281581

log10TL 2.9775185 3.1252230 3.2729275

ZoneP 0.1992625 0.4801723 0.7610822

log10TL:ZoneP -0.4086951 -0.2628585 -0.1170220

Random Effects:

Level: Family

lower est. upper

sd((Intercept)) 0.16999148 0.3152096 0.5844827

sd(log10TL) 0.08573837 0.1596196 0.2971647

cor((Intercept),log10TL) -0.99974099 -0.9986156 -0.9926182

Variance function:

lower est. upper

P 0.5294444 0.607688 0.6974946

Within-group standard error:

lower est. upper

0.02826388 0.03110539 0.03423257

This case study shows us how to model and interpret more than the fixed effects, especially how the variation could be explained. For example, the variance function tells us that the variation in the pelagic habitat is 0.6 times the variation in the littoral habitat. Modeling the variation of ecological data gives us a more complete understanding of the ecological processes at work.

# Visualization

datG$fit = predict(mod2H)

datG$res = residuals(mod2H)

ggplot(data=datG,aes(x=log10TL,y=log10M,col=Zone))+

geom_point(alpha=0.5)+

geom_line(aes(y=fit),linewidth=1)+

facet_wrap(~Family)+ #Optional

theme_bw()

This best model shows that we have a random variation of the length-mass relationship according to the family and that this relationship is different in the two types of habitat, the slope being slower in the pelagic habitat. We finish, however, with a general though: is the length-mass relationship is really different according to the habitat type or, alternatively, the relationship shift according to the size (total length) of the individual? Since the overlap of total length according to the habitat is low, we can completely distinguish these two possible explanations. This outlines the importance to have the right data in hand to answer ecological question.

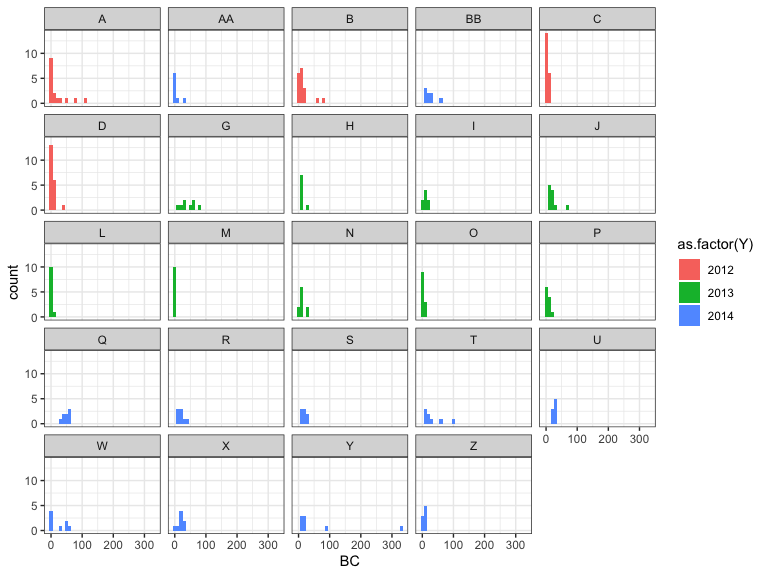

GLMM: brook charr abondance

The database could be found here: https://datadryad.org/stash/landing/show?id=doi%3A10.5061%2Fdryad.34tmpg4p8

In this case study, we will explore the relative abundance of brook charr in littoral habitat of Canadian Shield lakes. Details of the sampling design could be found in the original article (Rainville et al. 2022). In brief, brook charr were captured in 24 lakes and three consecutive years. This sampling design is thus typical of crossed design, year and lake including as random effects. We will focus here on the distribution of the response variable, extending LMM to GLMM.

Download and explore data

dat = read_excel("Data/Data_Rainville_et_al_2022_Evolutionary_Ecology.xlsx",

sheet = "BDlittoral")

dat$Temp = dat$T #Temperature variable

#Visualization: distribution of captures

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=BC,fill=as.factor(Y)))+

geom_histogram(binwidth=10)+

facet_wrap(~LC)+

theme_bw()

Negative binomial distribution

We will use the lme4 package. We don’t explore the influence of predictors in this example, but we will show how to deal with crossed design that is quite straightforward using lme4 package. Extending LMM to GLMM is also straightforward using the family argument to specify the distribution of the response variable. Since the response variable are the number of captures, appropriate distributions could be the Poisson or the negative binomial distributions. The negative binomial distribution can generally handle the overdispersion of ecological data and is often more appropriate than the Poisson distribution. As before, the two models can be compare using the anova function. For simplicity, we will not explore the potential relationship with the predictors (e.g., the temperature). Note that simulated values from LMM (i.e., normal distribution) are obtained with the simulate function and could be negative, which is not possible (number of captures cannot be negative). The negative distribution simulates more high abundances than the Poisson distribution.

#Normal distribution

mod.N = lmer(BC~1+(1|LC)+(1|Y),data=dat)

simulate(mod.N,nsim=5)[1:10,1:5]

sim_1 sim_2 sim_3 sim_4 sim_5

1 22.177275 -49.4177181 56.271410 34.687981 72.073170

2 17.024076 -0.1053373 5.234417 31.821681 33.430622

3 51.075015 -24.4760264 -5.222976 -10.643936 29.809958

4 -1.090146 15.3458591 16.145508 -10.633513 39.518018

5 38.434107 35.7595436 32.733063 8.619748 26.227723

6 -2.585815 -42.0272885 32.300223 -31.156558 43.610788

7 53.544889 11.1338845 13.311571 -4.676094 2.509264

8 29.041403 -5.6599222 -10.201517 -2.191722 78.587746

9 8.483316 -2.4866802 48.440083 50.946557 46.433534

10 -7.191438 25.7922704 3.240183 -13.671578 38.992284

#Poisson distribution

mod.P = glmer(BC~1+(1|LC)+(1|Y),data=dat,family="poisson")

simulate(mod.P,nsim=5)[1:10,1:5]

sim_1 sim_2 sim_3 sim_4 sim_5

1 18 112 4 14 10

2 18 97 3 15 8

3 14 90 3 18 6

4 22 93 2 16 12

5 16 82 2 15 8

6 24 80 2 20 6

7 21 105 5 12 10

8 29 87 2 17 4

9 13 88 5 14 8

10 14 82 1 18 5

#Negative binomial distribution

mod.NB = glmer.nb(BC~1+(1|LC)+(1|Y),data=dat)

simulate(mod.NB,nsim=5)[1:10,1:5]

sim_1 sim_2 sim_3 sim_4 sim_5

1 3 3 2 12 113

2 3 38 40 8 577

3 1 6 5 1 166

4 1 3 1 2 202

5 4 7 3 16 43

6 0 8 3 0 228

7 2 19 34 10 125

8 0 3 17 5 124

9 0 2 41 4 83

10 4 8 49 15 117

anova(mod.P,mod.NB)

Data: dat

Models:

mod.P: BC ~ 1 + (1 | LC) + (1 | Y)

mod.NB: BC ~ 1 + (1 | LC) + (1 | Y)

npar AIC BIC logLik deviance Chisq Df Pr(>Chisq)

mod.P 3 4335.2 4345.8 -2164.62 4329.2

mod.NB 4 1789.7 1803.8 -890.86 1781.7 2547.5 1 < 2.2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

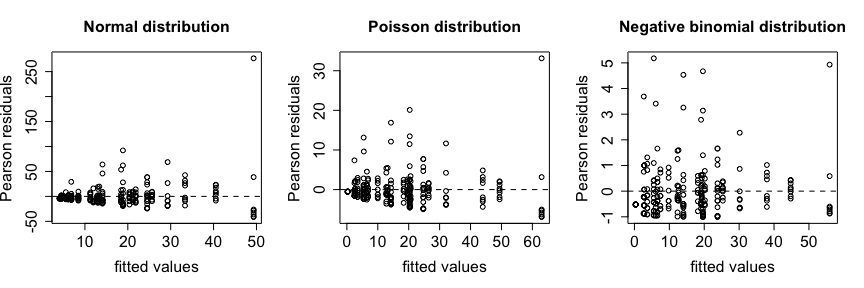

The negative binomial model outperforms the Poisson model. Plots of fitted values versus Pearson residuals show how residuals are reduced and better distributed for the negative binomial distribution.

You can use the summary function to look at the results of the model.

summary(mod.NB)

Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

Approximation) [glmerMod]

Family: Negative Binomial(1.0623) ( log )

Formula: BC ~ 1 + (1 | LC) + (1 | Y)

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

1789.7 1803.8 -890.9 1781.7 247

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-1.0084 -0.6210 -0.2681 0.3030 5.1776

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

LC (Intercept) 1.1406 1.0680

Y (Intercept) 0.1758 0.4193

Number of obs: 251, groups: LC, 24; Y, 3

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 2.3887 0.3419 6.987 2.82e-12 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Looking at p-vales of the fixed effect is not very meaningful (i.e., abundances is different from 0), however random effect show that variability is higher among lakes than among years.

The predict function is useful to obtain predicted values from the fitting model. The type argument is used to specify that we want predicted values on the original scale (i.e., the number of capture) whereas the re.form argument specifies how to deal with the random component: NA if we want to omit random effect and predict on fixed effects only, NULL if we want to predict considering all random effects, or a specific formula to indicate which random effect to consider in prediction. Note how the expand.grid function can be used to create a new data frame by considering the combination of variables included in the model.

newDat <- with(dat, expand.grid(LC=unique(LC), Y=unique(Y)))

newDat$predFix = predict(mod.NB,type="response",newdata=newDat,re.form=NA) #No random component

newDat$predRan = predict(mod.NB,type="response",newdata=newDat,re.form=NULL) #Full random components

newDat$predLC = predict(mod.NB,type="response",newdata=newDat,re.form=~(1|LC)) #Random component: lakes

newDat$predY = predict(mod.NB,type="response",newdata=newDat,re.form=~(1|Y)) #Random component: years

newDat[1:48,]

LC Y predFix predRan predLC predY

1 A 2012 10.89913 19.6258884 21.9914088 9.726754

2 AA 2012 10.89913 3.6094518 4.0445013 9.726754

3 B 2012 10.89913 14.0246398 15.7150383 9.726754

4 BB 2012 10.89913 14.0658020 15.7611617 9.726754

5 C 2012 10.89913 2.7984814 3.1357841 9.726754

6 D 2012 10.89913 5.5530209 6.2223299 9.726754

7 G 2012 10.89913 45.0371770 50.4655356 9.726754

8 H 2012 10.89913 14.9966975 16.8042587 9.726754

9 I 2012 10.89913 11.6287999 13.0304263 9.726754

10 J 2012 10.89913 22.6479304 25.3776994 9.726754

11 L 2012 10.89913 3.1772991 3.5602609 9.726754

12 M 2012 10.89913 0.4347612 0.4871632 9.726754

13 N 2012 10.89913 14.6509346 16.4168208 9.726754

14 O 2012 10.89913 4.3643540 4.8903923 9.726754

15 P 2012 10.89913 7.8086182 8.7497958 9.726754

16 Q 2012 10.89913 26.4542222 29.6427659 9.726754

17 R 2012 10.89913 11.9237583 13.3609362 9.726754

18 S 2012 10.89913 11.3996388 12.7736442 9.726754

19 T 2012 10.89913 17.8290762 19.9780257 9.726754

20 U 2012 10.89913 14.9658550 16.7696988 9.726754

21 W 2012 10.89913 14.0658020 15.7611617 9.726754

22 X 2012 10.89913 10.7415264 12.0362091 9.726754

23 Y 2012 10.89913 33.0505303 37.0341310 9.726754

24 Z 2012 10.89913 4.4000789 4.9304231 9.726754

25 A 2014 10.89913 33.2131390 21.9914088 16.460708

26 AA 2014 10.89913 6.1083209 4.0445013 16.460708

27 B 2014 10.89913 23.7340752 15.7150383 16.460708

28 BB 2014 10.89913 23.8037344 15.7611617 16.460708

29 C 2014 10.89913 4.7359054 3.1357841 16.460708

30 D 2014 10.89913 9.3974474 6.2223299 16.460708

31 G 2014 10.89913 76.2169837 50.4655356 16.460708

32 H 2014 10.89913 25.3791007 16.8042587 16.460708

33 I 2014 10.89913 19.6795650 13.0304263 16.460708

34 J 2014 10.89913 38.3273788 25.3776994 16.460708

35 L 2014 10.89913 5.3769835 3.5602609 16.460708

36 M 2014 10.89913 0.7357518 0.4871632 16.460708

37 N 2014 10.89913 24.7939618 16.4168208 16.460708

38 O 2014 10.89913 7.3858515 4.8903923 16.460708

39 P 2014 10.89913 13.2146233 8.7497958 16.460708

40 Q 2014 10.89913 44.7688146 29.6427659 16.460708

41 R 2014 10.89913 20.1787268 13.3609362 16.460708

42 S 2014 10.89913 19.2917527 12.7736442 16.460708

43 T 2014 10.89913 30.1723709 19.9780257 16.460708

44 U 2014 10.89913 25.3269056 16.7696988 16.460708

45 W 2014 10.89913 23.8037344 15.7611617 16.460708

46 X 2014 10.89913 18.1780208 12.0362091 16.460708

47 Y 2014 10.89913 55.9318301 37.0341310 16.460708

48 Z 2014 10.89913 7.4463091 4.9304231 16.460708

glmmTMB is another powerful package for GLMMs. The formula is quite similar to the lme4 package. You can consult the vignettes associated to this package for more details.

mod.P = glmmTMB(BC~1+(1|LC)+(1|Y),data=dat,family=poisson)

Binomial distribution

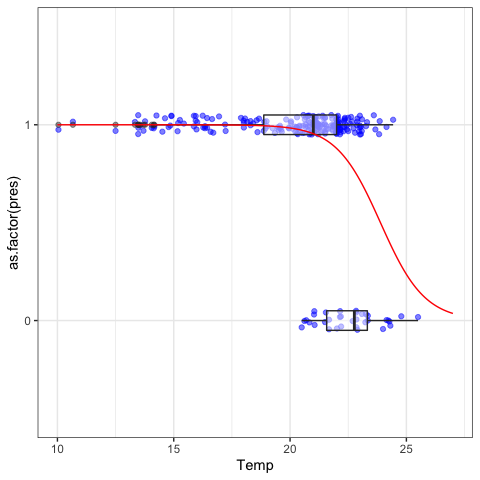

When the response variable is binary (e.g., presence/absence), the binomial distribution should be used. Here, we first transform the number of captures to a dummy variable (0 = no capture; 1: at least one capture). We then try to predict the probability to capture a brook charr in littoral habitat according to the temperature of the epilimnion (Temp variable).

dat$pres = ifelse(dat$BC==0,0,1)

#Analyses

mod.B = glmer(pres~Temp+(1|LC)+(1|Y),data=dat,family="binomial")

#Results

summary(mod.B)

Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

Approximation) [glmerMod]

Family: binomial ( logit )

Formula: pres ~ Temp + (1 | LC) + (1 | Y)

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik deviance df.resid

149.7 163.8 -70.9 141.7 247

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-4.3185 0.0232 0.1560 0.3582 1.2745

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

LC (Intercept) 1.5492 1.2447

Y (Intercept) 0.5855 0.7652

Number of obs: 251, groups: LC, 24; Y, 3

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 25.1542 6.2234 4.042 5.3e-05 ***

Temp -1.0531 0.2784 -3.782 0.000155 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

Temp -0.995

Temperature is highly significant, the coefficient being negative means that the probability of capturing a brook charr decreases as temperature increases. We can see this relationship on a plot.

#Visualization

newDat <- data.frame(Temp=seq(10,27,0.1))

newDat$predFix = predict(mod.B,type="response",newdata=newDat,re.form=NA)

newDat$x = 1 + newDat$predFix #just to add line on ggplot

ggplot(dat,aes(x=as.factor(pres),y=Temp))+

geom_jitter(col="blue",position=position_jitter(0.05),alpha=0.5)+

geom_boxplot(width=0.1,alpha=0.5)+

geom_line(data=newDat,aes(x=x,y=Temp),col="red")+

coord_flip()+

theme_bw()

NLME: walleye growth curve

The database could be found here: https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.vb957

In this third case study, we will extend the conceptual framework of fixed and random effects in the context of non linear mixed models using the nlme package. This is particularly helpful to fit theoretical models to ecological data. We illustrate the use of NLME by fitting von Bertalanffy growth curve (VBGF) on walleye data. Extensive analyses of the walleye growth curve could be found in the original article (Honsey et al. 2017).

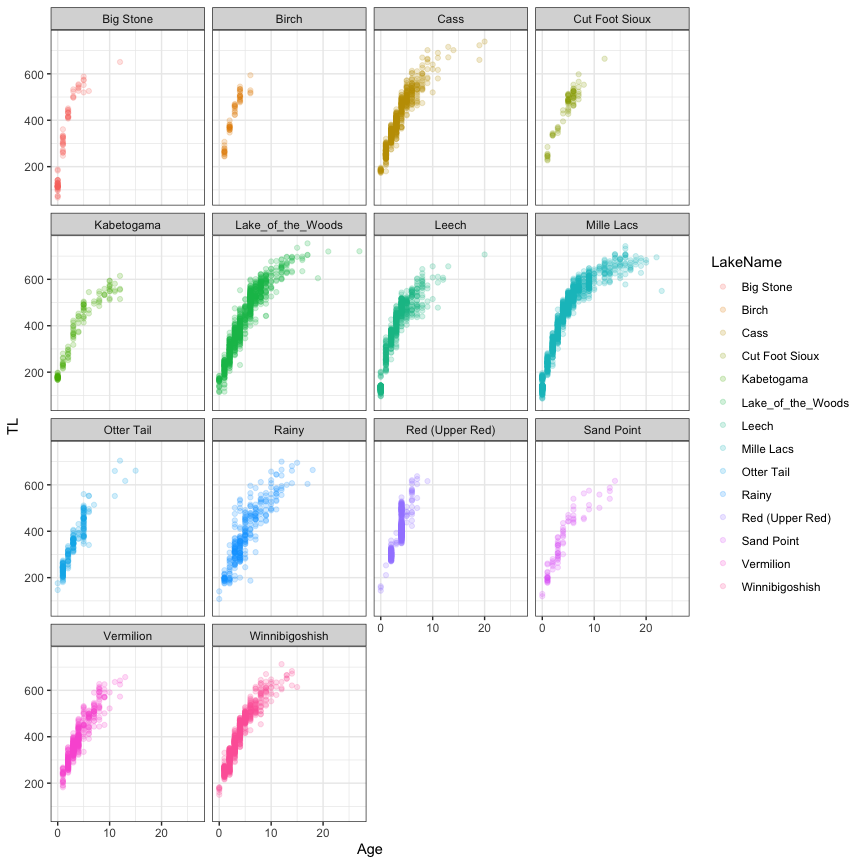

Download and explore data

dat = read_excel("Data/MN_Walleye_data_Honsey_et_al_Ecol_Apps.xlsx",sheet="Data")

dat$TL = dat$TotalLength

dat = dat[,-c(6,7)] #Remove Sex and Maturity that contain missing values

datG = groupedData(TL~Age|LakeName,data=dat)

#Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=Age,y=TL,col=LakeName))+

geom_point(alpha=0.2)+

facet_wrap(~LakeName)+

theme_bw()

VBGF

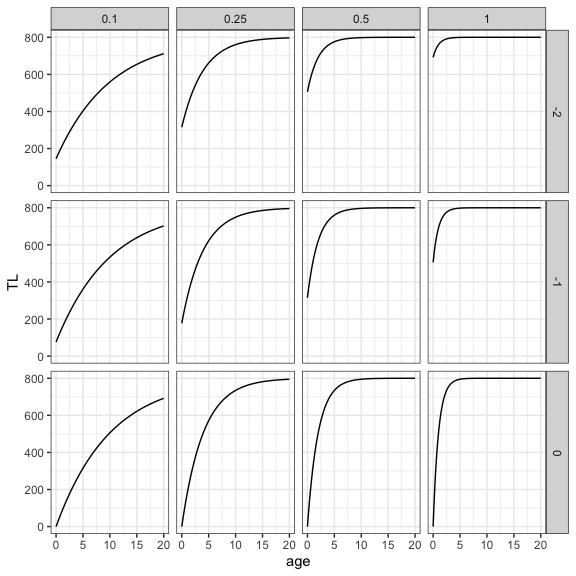

The VBGF is defined by three parameters: Linf, the asymptotic length, k, the growth coefficient, and t0, the theoretical age when size (total length) equals zero. The best way to understand how these parameters influence the VBGF is to first define the VBGF function and then visualize the growth curve for different values of the parameters. On the plot below, Linf is fixed to 800, k, ranges from 0.1 to 1 and t0, from -2 to 0.

#Define the von Bertalanffy function

VBGF = function(x,Linf,k,t0) Linf*(1-exp(-k*(x-t0)))

#Visualization

age = seq(0,20,0.1)

k = c(0.1,0.25,0.5,1)

t0 = c(-2,-1,0)

newDat = expand.grid(age=age,k=k,t0=t0)

newDat$TL = VBGF(x=newDat$age,Linf=800,k=newDat$k,t0=newDat$t0)

ggplot(data=newDat,aes(x=age,y=TL))+

geom_line(linewidth=1)+

facet_grid(t0~k)+

theme_bw()

## Warning: Ignoring unknown parameters: linewidth

nls and nlsList

The nls function can fit non linear model. Plotting the residuals according to the grouping variable informs us how it is important to incorporate the random effects to the model. Here, we see that residuals are not centered to zero for many lakes, indicating biases in model fit. Random effects have to be included in the model to improve model fit.

#nls

mod.nls = nls(TL~VBGF(Age,Linf,k,t0),data=dat,

start=c(Linf=800,k=.3,t0=-2))

summary(mod.nls)

Formula: TL ~ VBGF(Age, Linf, k, t0)

Parameters:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

Linf 686.20487 3.84292 178.56 <2e-16 ***

k 0.18346 0.00264 69.50 <2e-16 ***

t0 -1.31013 0.02532 -51.75 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 42.74 on 6232 degrees of freedom

Number of iterations to convergence: 4

Achieved convergence tolerance: 8.025e-06

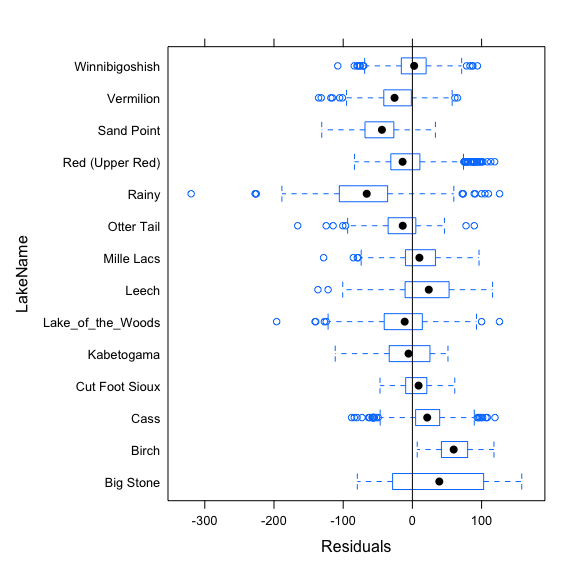

plot(mod.nls,LakeName~resid(.),abline=0)

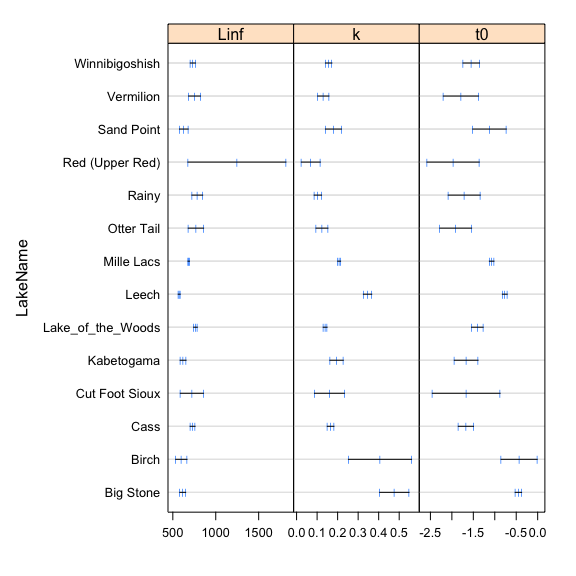

The nlsList function from the nlme package fits the non linear model by group and can be used to feed the NLME model. Plotting the estimates and confidence intervals of the parameters informs us which of the parameters should be incorporated to random effect into the model.

#nlsList

mod.lis = nlsList(TL~VBGF(Age,Linf,k,t0)|LakeName,data=dat,

start=c(Linf=800,k=.3,t0=-2))

mod.lis

Call:

Model: TL ~ VBGF(Age, Linf, k, t0) | LakeName

Data: dat

Coefficients:

Linf k t0

Big Stone 615.2847 0.47640877 -0.4496596

Birch 599.2751 0.40639674 -0.4326197

Cass 730.2746 0.16582262 -1.6728568

Cut Foot Sioux 721.9514 0.16013094 -1.6658202

Kabetogama 619.5719 0.19482829 -1.6663531

Lake_of_the_Woods 763.7969 0.13920308 -1.4058217

Leech 574.3497 0.34585097 -0.7668472

Mille Lacs 685.0770 0.20748989 -1.0721370

Otter Tail 768.9445 0.12378024 -1.9103712

Rainy 784.8787 0.10368433 -1.7118710

Red (Upper Red) 1246.5037 0.06944248 -1.9706741

Sand Point 628.2803 0.17967672 -1.1223282

Vermilion 752.8391 0.13023880 -1.7898292

Winnibigoshish 733.2848 0.15629007 -1.5480317

Degrees of freedom: 6235 total; 6193 residual

Residual standard error: 33.61449

plot(intervals(mod.lis),layout=c(3,1))

nlme

Since all the three parameters seem to vary by lake, we can fit the NLME with random effects for the three parameters. We can directly use the nlme function with the model coming from the nlsList object or writing the equation, specifying how to fit fixed and random components and initiate the starting parameters from the nlsList estimates.

mod.nlme = nlme(mod.lis)

mod.nlme = nlme(TL~VBGF(Age,Linf,k,t0),data=dat,

fixed = Linf + k + t0 ~1,

random = Linf + k + t0 ~1|LakeName,

start=fixef(mod.lis))

summary(mod.nlme)

Nonlinear mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood

Model: TL ~ VBGF(Age, Linf, k, t0)

Data: dat

AIC BIC logLik

61718.82 61786.2 -30849.41

Random effects:

Formula: list(Linf ~ 1, k ~ 1, t0 ~ 1)

Level: LakeName

Structure: General positive-definite, Log-Cholesky parametrization

StdDev Corr

Linf 73.50797185 Linf k

k 0.09675492 -0.750

t0 0.41455909 -0.628 0.921

Residual 33.63418459

Fixed effects: Linf + k + t0 ~ 1

Value Std.Error DF t-value p-value

Linf 701.3126 20.897026 6219 33.56040 0

k 0.2019 0.026457 6219 7.63013 0

t0 -1.3274 0.116774 6219 -11.36769 0

Correlation:

Linf k

k -0.744

t0 -0.634 0.900

Standardized Within-Group Residuals:

Min Q1 Med Q3 Max

-7.29496083 -0.58028176 0.01433836 0.60245254 5.87134241

Number of Observations: 6235

Number of Groups: 14

intervals(mod.nlme)

Approximate 95% confidence intervals

Fixed effects:

lower est. upper

Linf 660.3570955 701.3126299 742.2681643

k 0.1500165 0.2018684 0.2537203

t0 -1.5563106 -1.3274487 -1.0985867

Random Effects:

Level: LakeName

lower est. upper

sd(Linf) 45.70317142 73.50797185 118.2285990

sd(k) 0.06348487 0.09675492 0.1474606

sd(t0) 0.27409574 0.41455909 0.6270044

cor(Linf,k) -0.91421134 -0.75048764 -0.3761385

cor(Linf,t0) -0.87001051 -0.62825819 -0.1429577

cor(k,t0) 0.75534473 0.92084581 0.9759264

Within-group standard error:

lower est. upper

33.04661 33.63418 34.23221

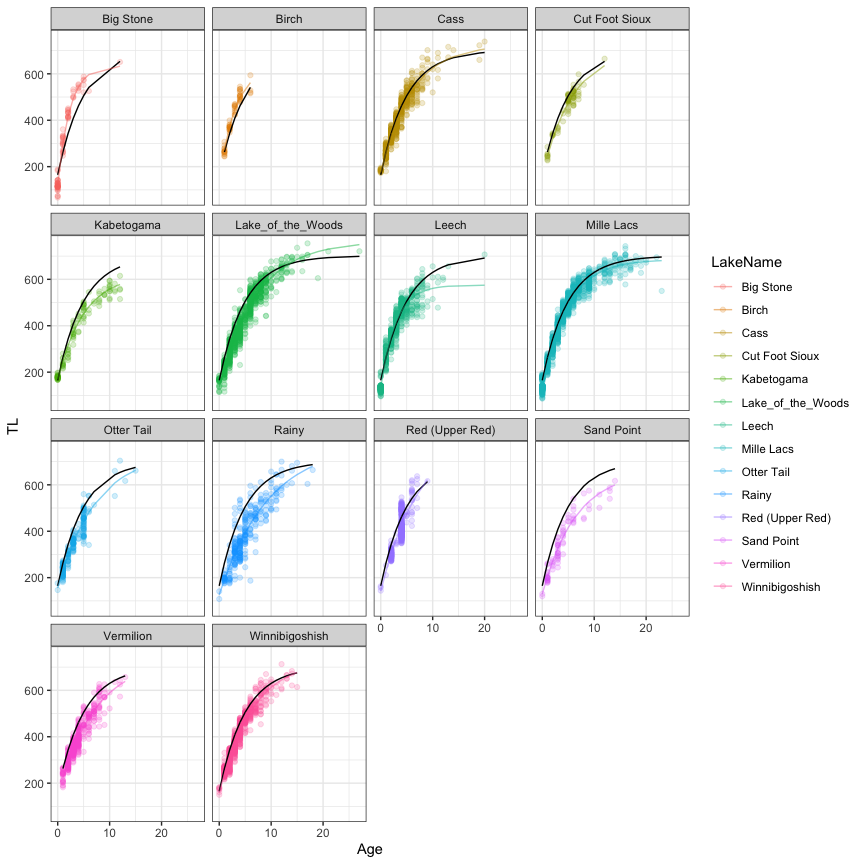

The summary function is used to show the model output and the intervals function, to extract the confidence intervals of the model parameters. We can visualize the results by calculating the predicted values at the population (black lines) or lake (color lines) levels as follow:

#Extract residuals and predicted values

dat$res = residuals(mod.nlme)

dat$predFull = predict(mod.nlme)

dat$predFixe = VBGF(dat$Age,fixef(mod.nlme)[1],fixef(mod.nlme)[2],fixef(mod.nlme)[3])

#Visualization

ggplot(data=dat,aes(x=Age,y=TL,col=LakeName))+

geom_point(alpha=0.2)+

geom_line(aes(y=predFixe),linewidth=1,col='black')+

geom_line(aes(y=predFull),linewidth=1,alpha=0.5)+

facet_wrap(~LakeName)+

theme_bw()

## Warning: Ignoring unknown parameters: linewidth

## Ignoring unknown parameters: linewidth

Note that we could smooth the lines by calculating predicted values on a new data frame by specifying regular intervals in age using the expand.grid function as illustrated in the GLMM case study. The parameters estimates at the lake level could be obtained with the coef function:

coef(mod.nlme)

Linf k t0

Big Stone 636.0669 0.4288756 -0.4916049

Birch 625.1030 0.3453633 -0.6424293

Cass 725.1959 0.1693830 -1.6279210

Cut Foot Sioux 704.4610 0.1723542 -1.4999589

Kabetogama 619.7784 0.1979797 -1.5987604

Lake_of_the_Woods 764.5359 0.1386047 -1.4208832

Leech 575.1076 0.3445203 -0.7696058

Mille Lacs 685.2610 0.2071741 -1.0767931

Otter Tail 738.3058 0.1363032 -1.7370665

Rainy 776.8366 0.1059113 -1.6781612

Red (Upper Red) 840.2491 0.1294834 -1.4276757

Sand Point 660.5877 0.1545496 -1.4147556

Vermilion 735.4408 0.1382678 -1.6648340

Winnibigoshish 731.4472 0.1573876 -1.5338316

Finally, different structures of the model could be compared by updating an existing model. Here, an example if we try to simplify the random component of the model:

#comparing model for the random component

mod.LKT = mod.nlme

mod.LK = update(mod.LKT,random = Linf + k ~1|LakeName)

anova(mod.LK,mod.LKT)

Model df AIC BIC logLik Test L.Ratio p-value

mod.LK 1 7 62056.94 62104.11 -31021.47

mod.LKT 2 10 61718.82 61786.20 -30849.41 1 vs 2 344.1205 <.0001

We confirm that we need a random effect for all parameters. We could also try to include predictors in the fixed effect. Be careful, however, to include the right starting parameter values. See the book of Pinheiro and Bates (2000) for detailed examples.

References

Allegue, H., Y. G. Araya-Ajoy, N. J. Dingemanse, N. A. Dochtermann, L. Z. Garamszegi, S. Nakagawa, D. Réale, H. Schielzeth, and D. F. Westneat. 2017. Statistical Quantification of Individual Differences (SQuID): an educational and statistical tool for understanding multilevel phenotypic data in linear mixed models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 8:257-267.

Bolker, B. 2009. Learning hierarchical models: advice for the rest of us. Ecological Applications 19:588-592.

Dingemanse, N. J., and N. A. Dochtermann. 2013. Quantifying individual variation in behaviour: mixed-effect modelling approaches. Journal of Animal Ecology 82:39-54.

Faraway, J. 2006. Extending the linear models with R. Chapman and Hall, Boca Raton, Floride.

Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2006. Data analysis using regression and multilevel / hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York.

Harrison, X. A., L. Donaldson, M. E. Correa-Cano, J. Evans, D. N. Fisher, C. E. D. Goodwin, B. S. Robinson, D. J. Hodgson, and R. Inger. 2018. A brief introduction to mixed effects modelling and multi-model inference in ecology. Peerj 6:e4794.

Honsey, A. E., D. F. Staples, and P. A. Venturelli. 2017. Accurate estimates of age at maturity from the growth trajectories of fishes and other ectotherms. Ecological Applications 27:182-192.

Johnson, P. C. D. 2014. Extension of Nakagawa & Schielzeth’s R2GLMM to random slopes models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 5:944-946.

Nakagawa, S., P. C. D. Johnson, and H. Schielzeth. 2017. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 14:20170213.

Nakagawa, S., and H. Schielzeth. 2013. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 4:133-142.

Pépino, M., P. Magnan, and R. Proulx. 2018. Field evidence for a rapid adaptive plastic response in morphology and growth of littoral and pelagic brook charr: A reciprocal transplant experiment. Functional Ecology 32:161-170.

Pépino, M., M. A. Rodríguez, and P. Magnan. 2016. Assessing the detectability of road crossing effects in streams: mark–recapture sampling designs under complex fish movement behaviours. Journal of Applied Ecology 53:1831-1841.

Pinheiro, J. C., and D. M. Bates. 2000. Mixed-effects models in S and S-plus. Springer, New York.

Rainville, V., A. Dupuch, M. Pépino, and P. Magnan. 2022. Intraspecific competition and temperature drive habitat-based resource polymorphism in brook charr, Salvelinus fontinalis. Evolutionary Ecology 36:967-986.

Reyjol, Y., M. A. Rodriguez, N. Dubuc, P. Magnan, and R. Fortin. 2008. Among- and within-tributary responses of riverine fish assemblages to habitat features. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 65:1379-1392.

Schielzeth, H., N. J. Dingemanse, S. Nakagawa, D. F. Westneat, H. Allegue, C. Teplitsky, D. Réale, N. A. Dochtermann, L. Z. Garamszegi, and Y. G. Araya-Ajoy. 2020. Robustness of linear mixed-effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1141– 1152.

Schielzeth, H., and S. Nakagawa. 2013. Nested by design: model fitting and interpretation in a mixed model era. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 4:14-24.

Wagner, T., D. B. Hayes, and M. T. Bremigan. 2006. Accounting for multilevel data structures in fisheries data using mixed models. Fisheries 31:180-187.

Zuur, A. F., and E. N. Ieno. 2016. A protocol for conducting and presenting results of regression-type analyses. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7:636-645.

Zuur, A. F., E. N. Ieno, N. J. Walker, A. A. Saveliev, and G. M. Smith. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York, New York, USA.